Reindeer Lichen

Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia rangiferina) is a light-colored, fruiticose, cup lichen in the family Cladoniaceae. Like other lichen species, they are composed of a fungus and an algae living together in a symbiotic, or mutually beneficial relationship. Unlike mosses, lichen do not have any roots, stems or leaves and their chloroplasts are contained only in the algae on the top surface of the lichen. This species grows in both hot and cold climates in well-drained, open environments. Reindeer lichen can be found in the Arctic tundra, Canadian boreal forests, and spread throughout the northeastern United States. As the common name suggests, it is an important food for reindeer (caribou) and is economically important as a result. (posted 12/13/2023)

Birding Expedition Highlights

Limpkin

On a recent Fall Birding Expedition, a monthly all-day bus trip run by the Park System that searches for birds around the state, we had some incredible luck. We started our morning in Monmouth County and found a Limpkin. It was the first record for this species in the state. Limpkins prefer tropical wetlands habitats. They are usually found in the United States only in Florida and part of Georgia. Outside of the United States, they are found in Central and South America.

We unexpectedly found our Limpkin feeding on invertebrates in the grass of a local park in Wall Township. In recent years, it is thought that the introduction of an invasive apple snail in the United States has allowed Limpkins to become an extra vagrant species as this new food source has become available. In fact, they have been found in 26 states and two Canadian provinces.

Although in appearance Limpkins resemble Ibis, herons, and egrets; they are more closely related to rails and cranes. They have a long neck, a long and heavy yellowish bill, white spotting on their back and sides, and overall brown color. These long-legged birds are easily identified when found in marshes and swampy forests.

Cattle Egret

We found our second rarity of the day while still in Monmouth County. This time it was a Cattle Egret that was hiding along the small marsh found at the National Guard Training Center in Sea Girt. The Cattle Egret is a small, compact, stocky white egret with yellow bill. With its non-breeding plumage, it has all black legs and feet and prefers upland habitat. It resembles the more common Snowy Egret, which is also white but has a black bill, black legs, and golden colored feet; and likes wetland habitats. They are typically found further south and occasionally spotted during migration as they sometimes tend to wander.

Sage Thrasher

Our third highlight of the day was found along the Wildlife Drive at the Edwin B. Forsythe Wildlife Refuge in Atlantic County. We encountered a Sage Thrasher - a bird usually found on the West Coast of the United States. This is only the fifth record for this bird species in New Jersey. Thankfully with a little patience and luck, the bird was very obliging and came out along the grasses and gave us some close views and photo opportunities.

Sage Thrashers are the smallest of the thrasher species found in the United States. It has a short bill, a heavily streaked breast, a greyish-brown back, two thin white wing bars, and pale eyes. They are usually found standing erect on the ground or on a short perch in sagebrush habitats.

Other highlights of this fantastic trip include a Rough-legged Hawk and a Short-eared Owl that was hunting over a marsh as we stood on a small boardwalk perch. Throughout the day, we saw and heard 89 species - including some incredible rare birds – that made for a memorable outing. Visit our Programs & Registration page and search "birding" for our upcoming birding trips and walks. (posted 12/23/2023)

Sun Halo

Photo courtesy of Neal Fitzsimmons

On a recent Casual Birder walk, we visited Fisherman's Cove Conservation Area and were given the added bonus of not only finding interesting bird species but an extra interesting meteorological phenomenon of seeing a sun halo formed in the sky as we walked along the shoreline.

The optical effect that causes a sun halo is quite rare, but it can happen when ice crystals form in the sky and refract, acting like a prism breaking visible light into its color components. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a halo is a ring or light that forms around the sun or moon as the sun or moon light refracts off ice crystals present in a thin veil of cirrus clouds. The halo is usually seen as a bright, white ring although sometimes it can have color. (posted 12/12/2023)

White-faced Ibis

While you may be tempted to stay indoors during the cold weather, there are plenty of reasons to head out into the field this winter! Recently, a juvenile White-faced Ibis was found at the Manasquan Reservoir along the shoreline close to the Environmental Center. It was seen feeding in the shallows, where ice had started to creep in along the edge. While the more common and expected species to find in Monmouth County is the Glossy Ibis; fall is a good season for rarities showing up. The features that helped us identify the White-faced Ibis were its reddish colored legs, overall pale brown color, paler cheeks, grey bill, and red-based dark eye color. We also heard its higher pitched calls in the field. (posted 12/12/2023)

American cranberry Vaccinium macrocarpon

The cranberry is a native fruiting plant of North America. New Jersey is currently the third largest cranberry producing area in the United States behind Wisconsin and Massachusetts. Cultivation in NJ is believed to have started in 1840. They were sold as fresh berries in barrels of cold water to ship merchants. The fruit’s high amount of vitamin C helped to ward off scurvy which plagued seafarers on their long trips. In modern times, we associate this fruit with cranberry juice or cranberry sauce, a Thanksgiving staple in many households.

Cranberry plants bloom during June and July and it takes about 80 days to develop fruit. Occurring from September to October, there are two methods to harvest the berries. The less common method is dry harvesting in which the fruit is “combed” from the vines using a specialized picking machine. The more common method is wet harvesting in which the plant beds are flooded, and the fruit is beaten off the vine. Due to pockets of air inside the fruit, berries float to the water’s surface and get corralled. They will then be loaded onto trucks and sent to a receiving station. Wet-harvested fruit is used for processed cranberry products like juice and sauce, whereas, dry harvested fruit is primarily sold fresh.

Other than harvest time, good drainage in the soil is essential to proper root growth and function. During that part of the season, commercial cranberry bogs are managed with drained soil and are not flooded for extended periods as a rule. Flooding is mainly confined to winter protection, harvest, and several specialized pest-control floods. (posted 11/27/2023)

Birds of a feather flock together is an English proverb that describes how similar things tend to congregate. Just watch as birds gather in large flocks during times of migration in the spring and fall. However, it’s the exception to this saying that can really grab your attention!

This is especially true when bird watching as sometimes a bird will get lost and, while looking for safety in numbers, join a different flock. Experienced birders know to scan through a flock and look for an outlier. Occasionally, they’ll be rewarded for their effort.

That's just what happened when Park System staff Rob Fanning spotted a Yellow-headed Blackbird in a large flock of Brown-headed Cowbirds and European Starlings yesterday. This male individual stood out from the crowd with its beautiful yellow/orange head coloration, white wing patches in flight and overall larger size.

With its colors reminiscent of a costume, this was a real Halloween treat for local birders as the Yellow-headed Blackbird is not often found on the East Coast. Its range is more central and western North America. (posted 11/1/2023)

Western Flycatcher

Recently, a Western Flycatcher was spotted at the Gateway National Recreation Area - Sandy Hook in Monmouth County. If accepted by the New Jersey Rare Birds Record Committee, this sighting would be only the sixth record of Western Flycatcher for New Jersey and the second ever for Monmouth County, with the first in early November of 2020 at the Dorbrook Recreation Area, Colts Neck.

It is especially interesting because two species, the Pacific-slope Flycatcher and the Cordilleran Flycatcher, that were considered separate species since 1989 were lumped together to become one species - the Western Flycatcher - by ornithologists this year. In very basic terms, this change was based on newly discovered genetics data as well as discovering overlap and interbreeding in part of their breeding ranges. Perhaps one day with enough time and geographic isolation, these two populations will once again be considered unique and we will regain a species for North America.

While Flycatcher identification can be quite difficult, the key identifying features for this bird are: an empid with bold whitish teardrop shaped eye ring, a generally low contrast appearance overall with greenish/olive upperparts, dull brownish wings/tail, dusky vest, a pale yellow wash through much of its undersides, slight raggedy crest, completely orange lower mandible, and whiteish wing bars with dull wing panel contrast and medium length primary projection. This bird also occasionally displays distinctive upward tail popping behavior typical of Western Flycatcher and wing flicking. Its discovery falls within the expected late fall/winter timing when vagrant Western Flycatcher species appear along the East Coast. (posted 10/30/2023)

Hawthorn

Fall is one of our most striking seasons with the deciduous trees changing their leaf colors from green to yellow, orange, and red. Some trees have those stunning fall colors on more than just their leaves. The Crataegus genus is a unique category featuring several hundred tree and shrub species; many of which bear fruit ripening in the fall with crimson and yellow colors to match the season. They are very difficult to tell apart and are offer referred to as a collective “Hawthorn.” All hawthorns have alternate, toothed, incised or lobed leaves. They bear clusters of showy white, pink or red flowers from May to June. The one pictured above is blooming late in the season and what a beautiful sight to see! Also pictured are the small orange or red apple-like fruits which are about 0.3-0.8 inches in diameter. (posted 10/23/2023)

Milkweed Tussock Moth

While gardening along the Huber Woods Discovery Path, the Tuesday Gardening Team spotted some caterpillar frass on the milkweed leaves. We assumed it was left by a monarch but to our surprise, a very different caterpillar appeared! Meet the Milkweed Tussock Moth, Euchaetes egle. We counted over 20 caterpillars on just four milkweed stalks.

The Milkweed Tussock Moth can host on any plant in the milkweed and dogbane category. Whereas monarch caterpillars prefer younger fresher foliage, this caterpillar feeds on older leaves which ensures no interspecies competition. Funny how that works! Similar to the monarch, by feeding on milkweed leaves the caterpillars themselves become less palatable to predators.

Milkweed Tussock Moths are covered in tiny hairs. These hairs will actually irritate a person’s skin, therefore, it is advised to admire these insects from afar. Once they mature into adult moths, they sport a light grayish brown color, which is perfect for daytime camouflage.

Seeing these caterpillars this time of year is such a treat! Since the milkweed plants are starting to enter fall dormancy, there is no concern about the caterpillars killing off the plants. The milkweed will come right back next spring. (posted 9/20/2023)

Spiders

Spiders have adapted to live in almost every type of land habitat and are found on every continent except for Antarctica. Globally, there are over 50,000 species documented to date. They are most known for creating intricate webs using their specialized organs called spinnerets that secrete a sticky proteinaceous silk to catch their prey.

When the light shines on a spider’s web in just the right way, it can be a magical sight to see. As you walk by, the light shines slightly different, making the web almost invisible. Webs are best seen in the early morning, since the spider will spend all night making it. Different spider species will create different web shapes.

Web patterns include “the classic” spiral orb web, the tangle web, funnel webs, tubular webs, and sheet webs. However, many species do not create webs and instead have adapted other more active hunting practices. Some will hide behind “trapdoors,” then jump or ambush their prey; some burrow in the ground; and some run fast to catch their prey. (posted 9/14/2023)

Katydids

Katydids are mostly nocturnal insects within the Phylum Arthropoda. They are in the family Tettigoniidae along with bush crickets and long-horned grasshoppers. As seen in the photo above, they have perfected the art of camouflage with their beautiful leaf-textured body. The adults will die off in fall but the eggs, hidden in vegetation, will overwinter.

In the spring, the nymphs will hatch and eat the same plants that the adults did. Nymphs lack the wings and reproductive organs; these parts will be added as the insect grows and sheds its exoskeleton. The males will start to sing as they become sexually mature. Each Katydid has its own rasping song, produced by rubbing their forewings together. Their singing occurs during their mating season, which is generally August through mid-October.

The tempo of their music speeds up on hot summer nights and slows down as the nights start to become cool. To most observers, their call sounds like, “katy-did, katy-didn’t” and coincide with other familiar sounds of summer like cicadas and frog calls. (posted 8/8/2023)

Amanita Mushroom

The Amanita genus contains about 600 species of mushrooms worldwide, and is also the one responsible for approximately 95% of fatalities that result from mushroom poisoning. Foraging has become very popular in recent years, and while it can be a rewarding way to gather natural foods, it must be done in a safe and careful manner. Before foraging, it's important to thoroughly research the mushrooms in your area and how to properly identify them. Many mushrooms can look like others that are inedible or toxic, and the consequences of misidentification can be severe. Yet even though many species are unsafe for human consumption, Amanita mushrooms are eaten by deer, squirrels, turtles, birds, and even some insects. (posted 7/5/2023)

Fall Flowers in July?

If you walk along the Huber Woods Discovery Path this month, you’ll notice a familiar flower blooming in the gardens. This is a goldenrod, but not just any goldenrod. Whereas most goldenrod species bloom in autumn, Early Goldenrod Solidago juncea is aptly named because it begins blooming in July!

Like all other goldenrod species, they are a pollinator magnet for all kinds of insects. After standing in front of these flowers for just two minutes, I witnessed dozens of bumblebees, countless smaller bees such as miner bees, and one monarch all enjoying some nectar and pollen! (posted 7/5/2023)

Groundhogs

Groundhogs, also called woodchucks, are the largest rodent within the squirrel family and are only found in North America. They are best known for predicting the winter forecast on Groundhog’s Day; although, they do not have a good track history of correct predictions.

Adult groundhogs weigh around 13 pounds and are an average length of 17-24 inches long. Just like squirrels, they have a long tail that’s about 7-9 inches in length. They use their sharp claws to dig large burrows in the ground that can be up to 6 feet deep and 20 feet wide. Groundhogs will commonly have multiple entrances/exits to the same burrow. Not only are their underground burrows protection from predators but it’s also a place to store their food and raise their young.

These solitary creatures hibernate in the winter - they have the ability to slow their heartbeat from 80 beats per minute down to 5 beats per minute - slowing their respiration and dropping their body temperature in order to survive the colder winter weather.

One last interesting fact – since groundhogs are rodents, they are polyphyodonts. That means their teeth continue to grow throughout their lives (unlike humans that have baby teeth that fall out and are replaced by our adult teeth). Scientists believe that by studying polyphodonts, they may be able to isolate the gene causing continual tooth growth and find a way to regenerate teeth in people who have lost them. (posted 6/20/2023)

Horseshoe Crabs

Recently, a few Park System Naturalists had the opportunity to participate in a workshop centered around an ancient animal - the horseshoe crab. Throughout the workshop, we participated in lectures, field excursions, and hands-on activities revolving around this magnificent creature.

One of the more distinctive parts of the workshop was observing horseshoe crab behavior and witnessing thousands of horseshoe crab eggs upon the shore. In late spring and early summer, when a high tide and new or full moon occur, horseshoe crabs journey to the sandy shores of New Jersey’s coastal bays and beaches to spawn.

Horseshoe crab eggs

During the spawning event, which can last a few nights, a female horseshoe crab can lay up to 100,000 eggs or more! Not only is this important for the species itself, but the mass number of eggs is a major food source for migrating and resident shorebirds. For this reason, horseshoe crabs are a vital part of the ecology of coastal communities. Here’s to another successful few hundred million years for this incredible animal!

Common Hackberry

Identifying a tree just by its bark can be difficult, but there is one tree that has very distinctive bark - the Common Hackberry. This native tree has a mixture of smooth gray bark with deep ridges and develops warty bumps as it ages. Some other names that the hackberry goes by are beaverwood, sugarberry, nettle tree, and northern/American hackberry.

Pictured in the second image are green berries that will eventually turn a purplish red color and become very sweet when ripe in the early fall. They are an important food source in the winter for many species, ranging from caterpillars to migrating birds like cedar waxwings. You can visit the pictured hackberry at

Huber Woods Park, Middletown, outside the Environmental Center. Be sure to stop in and say hi to the staff! (posted 6/1/2023)

Great Horned Owl Rescue

Recently, a Great Horned Owl pair built a nest on the Cove Trail at

Manasquan Reservoir, Howell, in a pitch pine and had at least one egg hatched. The hatchling was observed by Park System Naturalists and birders for several weeks. Approximately five weeks after hatching, the fledgling began the process of “branching,” where it moves to branches near the nest and practices flying.

On May 5, 2023, several park patrons noticed that the fledgling was on the ground near the nest. Normally, this is not unusual. As a young owl starts flying, at 9-10 weeks old, it's often on the ground while still being cared for by the parents. However, park patrons were concerned that this young owl may have been injured and notified Park System Rangers and Naturalists and Dr. Jennifer Mei-An Raicer, DVM, a local veterinarian who volunteers with local wildlife rehabilitators.

On the advice of Donald Bonica, a well-known raptor rehabilitator, Dr. Raicer met Park System staff at the nest site. After evaluating the situation, including its proximity to the trail and risk of disturbance, a decision was made to transport the owl to the Toms River Avian Care facility. With the assistance of Park Ranger Cory Krieger, Dr. Raicer caught the owl for transport.

At the facility, the fledgling will be fostered by an adult female Great Horned Owl. This adult owl, who cannot be released, acts as a foster mother for several young owls. After a few weeks of learning to fly and hunt, the young owl will be released. (posted 5/11/2023)

Wool Sower Gall Wasps

Galls are abnormal plant growths created by insects, mites, nematodes, fungi, bacteria and viruses. They can be caused by feeding or by egg-laying of insects and mites. The numbers of galls vary from season to season and, surprisingly, insect galls rarely affect the plant’s health. Depending on what makes it, galls come in many types and forms. Some are brown paper-like balls, fuzzy flower-like formations, or even spindle shaped. They can be found on tree trunks, branches, twigs and leaves.

Wool Sower Gall Wasps (Callirhytis seminator) have a complex life cycle in which they create different types of galls in alternating generations. The first wasps that emerge will lay eggs and create a leaf gall. Once those wasps develop, they will in turn lay their eggs on a white oak twig and create a new stem gall, as seen in the above picture. This specific gall is only found in the spring.

Inside are small seed-like structures in which the larvae will develop. Nicknamed “a toasted marshmallow,” this puffy ball found on the tips of white oak twigs is essentially an insect nursery for the Wool Sower Wasp. For the developing wasp grubs inside, the inner tissue of the gall provides tasty nutrients as well as a safe protective environment to live in until they reach their adult stage.

Adult wasps are about 1/8 inch long, dark brown and have flattened abdomens from side to side. Unlike other insects, these wasps do not bite or sting, and pose no threat to humans. (posted 5/2/2023)

Solitary Sandpiper

Though the weather has kept human park visitors off the trails, some of our wildlife visitors have enjoyed the rain. This migrating solitary sandpiper took a pit stop along a trail in a saturated field at

Thompson Park, Lincroft, to forage for bugs. (posted 5/2/2023)

Poison ivy is a plant with a notorious reputation and for good reason. All parts of the plant – the leaves, stems, and roots – contain urushiol. Urushiol is the chemical that causes the well-known allergic reaction of an itchy rash, but don’t let this prevent you from enjoying the great outdoors.

With appropriate identification, you can enjoy all that the trails have to offer without the worry of finding yourself in an itchy situation. As seen in this picture, poison ivy has three leaves, although more appropriately described as three leaflets. The edges of the poison ivy leaflets are key in correctly identifying the plant. Often, one edge of each leaflet will have a jagged edge while the opposite edge is either smooth or just barely jagged. Leaf color can vary as some leaves will be glossy while others are dull.

Additionally, the plant can be identified by the way it is growing. Poison ivy is a climbing vine that grows up trees and spreads across the forest floor. Lastly, poison ivy grows in many different environments. We see this plant growing at the beach, in our backyards, and even in our cities. As the saying goes, “leaves of three, let it be.” (posted 5/1/2023)

British Solider Lichen

Pictured above is British solider lichen, Cladonia cristatella, named after the red structures at the ends of the green/greyish branches, which resemble red-capped soldiers. The cap is called an apothecium and contains spore-producing reproductive parts. Lichen won’t get that scarlet cap until it’s at least four years old.

Lichen is composed of two different organisms - algae and fungus - living in symbiosis. Both need each other to survive. The fungus provides minerals and a structure, and the algae photosynthesizes to make food to share.

Lichen grows in a variety of habitats but most are found on trees, exposed rock surfaces, or dead wood like this fence at

Huber Woods Park, Middletown. (posted 4/28/2023)

Foamflower

This spring bloomer made a surprise appearance on this week’s

Spring Wildflower Hike at

Clayton Park, Upper Freehold.

Tiarella cordifolia, commonly known as Foamflower, is a low-growing perennial which sends up a lovely white flower in spring. This plant, like many other woodland bloomers, takes advantage of all the sunlight hitting the ground floor before all of the canopy trees fully leaf out. Bees and other pollinators consider this plant a valuable source of early season nectar.

Consider growing this native plant at home in your shadier areas. It can spread and act as a nice ground cover, although be aware the deer have been noted to enjoy the plants as well. Happy Spring! (posted 4/20/2023)

Early Spring Frogs Calling

Spring Peeper

Wood Frog

Spring is in the air and so are the calls of wood frogs, spring peepers, and New Jersey chorus frogs. These amphibians usually begin calling in mid-March, but New Jersey chorus frogs may call as early as February.

Wood frogs breed only in vernal wetlands, temporary wetlands that form from spring rains and snow, and are vital to several amphibian species. Spring peepers can also be heard calling from vernal wetlands, but they are not particular and will use any body of freshwater to breed.

These frogs each have their own call. The call of the wood frog is a duck-like quacking while tiny spring peepers, as their name implies, peep loudly. The New Jersey chorus frogs have repeated creaking sound like fingernails on a comb. (posted 3/30/2023)

Grape Hyacinths

Spring is in full force throughout our parks. Our resident birds are returning and so many of our spring flowers are in bloom. One small but beautiful perennial is the muscari, commonly known as grape hyacinths (Muscari armeniacum). They grow to be about 6-9” tall and look like mini clusters of cobalt blue bells that give off a grape juice fragrance.

Muscari contain anthocyanins, pigments responsible for blue, red, and purple fruits and vegetables. When this pigment is extracted, normally from boiling, it can be used as a pH indicator and makes for a fun at home science experiment. The pigment will either turn pink when exposed to an acid like lemon juice or blue-green when exposed to a base like baking soda. A common vegetable that you can try this with is a red cabbage, and when you’re done, it can be used as a natural dye! (posted 3/28/2023)

Garter Snake

This garter snake (

Thamnophis sirtalis) was enjoying the beautiful spring weather as it was seen sunning itself just off trail at the

Manasquan Reservoir, Howell. The garter snake is one of the smaller snakes we find in Monmouth County, growing to be around 20-30 inches.

Although small, this snake has an excellent way to deter predators from making it their next meal. Whenever a garter snake feels threatened, it will emit a foul-smelling musk. This defense mechanism comes in handy as the garter snake is prey for many animals such as hawks, crows, foxes, raccoons and, even, bullfrogs. As you can see pictured above, this snake has excellent camouflage, which only adds to its ability to escape predation. (posted 3/28/2023)

Spring Beauty

Now that spring is officially here, we welcome back a classic ephemeral flower, Spring Beauty, Claytonia virginica. As you walk among trees with dappled light, keep your eyes towards the ground as these flowers rarely get taller than six inches. The five petals can range in color from white to a soft pink. The bloom period usually lasts about a month, and by late spring these plants will go dormant until next year.

Spring Beauty is a vital source of pollen and nectar for insects emerging this time of year. Both native bees and flies are frequent visitors to this flower. One specialist bee, the Spring Beauty Miner Bee Andrena erigeniae requires the Spring Beauty’s pollen to feed its young. Without this flower, the Spring Beauty Miner Bee cannot exist. This story of connection is just one of thousands happening all around us, some of which are yet to be discovered! (posted 3/27/2023)

Red Maple

It’s officially time to slow down our busy lives and admire the spring blossoms. Pictured above, Red Maple

Acer rubrum is one of the earliest trees to blossom every spring. Each reddish flower is roughly just a quarter-inch in size, often growing in clusters of same sex flowers.

Pictured here are male flowers, which can be identified by the narrow stamens and yellow anthers on the tips. As a pollinator rubs against the anthers, pollen is transported via that animal’s body to a female flower, where fertilization can take place. In exchange, the pollinator is treated to a rewarding sip of nectar. Red Maples typically prefer moist soils, growing near streams, ponds, and other low lying areas. Fun fact- while Sugar Maples get all the attention, Red Maple trees can be tapped for syrup. You’ll just need a larger quantity of sap to make the syrup overall. People aren’t the only ones to enjoy this sweet treat, wildlife including Woodpeckers will peck into maples to sip it up. (posted 3/21/2023)

Snowdrops

There is nothing more delightful than the reawakening of life during a time of year where the landscape is still quite barren. Seen as early as late January, snowdrops are surely a welcome sight. With their blooms, they bring a feeling of hope and promise of spring. Native to Europe and the Middle East, snowdrops are very popular in the northern United States and have naturalized widely.

As this plant prefers winter sun and summer shade, it does particularly well under deciduous trees. They have become an integrated part of our ecosystem and can be found carpeting the forest floor or sprinkled throughout the landscape. This particular plant was seen at the Huber Woods Environmental Center, Middletown, but can also be seen along the Perimeter Trail at the Manasquan Reservoir, Howell. (posted 2/23/2023)

What’s That Smell?

Looks like spring may be coming early, which is the opposite of what some of our famous prognosticating rodents have predicted. Pictured here is the flower bud of an eastern skunk cabbage plant. It gets its name from the unpleasant “skunk” scent that it emits to attract pollinators like carrion beetles and flies. Usually found in moist habitats like swamps, wetlands, and alongside streams, this one was spotted in the Timalot section at Huber Woods Park. It’s one of the first native perennials to bloom in early spring and can emerge as early as February. Although it has been unseasonably warm this winter, cold is not a problem for skunk cabbage. It is one of the few plants that can exhibit thermogenesis, the ability to generate heat. It can warm up to 70 degrees Fahrenheit, melting any surrounding snow or frost. (posted 2/17/2023)

Huber Woods Park - Forestry Mowing

If you visit Huber Woods Park, you may notice portions of the tree line appear quite differently. This is the result of forestry mowing, the first step in the Park System’s initiative to reduce the ecological toll brought about by invasive plants. Throughout the Garden State, wild spaces are under siege by aggressively spreading nonnative plant species, and the Monmouth County Parks are no different. Following the forest mowing stage, carefully planned herbicide applications and plantings of native species will ensure a healthy ecosystem in years to come.

There are multiple factors at play, all of which align to give invasive species a competitive edge over our native ones. Many of the invasive plants in New Jersey originate from regions of Europe and Asia with very similar climates. However, these plants have made their way overseas without any of their respective herbivores to keep their populations low. Deer herbivory also plays a role, as these plant eaters highly value native plants as opposed to unfamiliar invasives. Additionally, research shows that prior land use and the mistreatment of soils play major roles in facilitating the establishment of invasive plants.

Pictured above are the invasive species Porcelainberry, Multiflora Rose, and Mugwort. Together they work to outcompete native plants, creating large swaths of low biodiverse terrain. While invasive species may look pretty, they provide little to no benefits to local ecosystems. For example, our specialist pollinators cannot use the pollen, nor can our butterflies use them as host plants.

While all of this may seem daunting, with vigilance and hard work we can promote a healthy ecosystem with a robust biodiversity. For more information about the Park System’s efforts in Huber Woods Park and other Park System sites, please call 732-842-4000, ext. 4258. (posted 2/15/2023)

Holding On Through Winter

Fastidious lawn rakers may be frustrated by deciduous trees that hold onto some of their dried, brown leaves only to drop them closer to spring, but leaves left hanging throughout the winter may serve a purpose or two. Marcescence is the name for this phenomenon, and beeches and oaks are tree species that commonly exhibit it. One theory for dead leaves that persist through winter is that they discourage browsing animals, like deer, from dining on tender branch tips. Another theory for marcescence: leaves that remain to fall off in the spring help to fertilize the ground and retain ground moisture during the warm growing season.

Park System Naturalist Sue Fertig showing marcescent beech leaves to young patron at Freneau Woods Park on 1/1/2023.

Park System Naturalist Sue Fertig showing marcescent beech leaves to young patron at Freneau Woods Park on 1/1/2023.

Marcescent leaves on oak tree, Hartshorne Woods Park, 1/14/2023

American beech tree with marcescent leaves, Huber Woods Park, 1/27/2023

Look carefully because a few of those hanging winter leaves may be hiding overwintering insects. The cocoons of the Promethea Moth (

Callosamia promethea) pictured below are examples of this leafy disguise. In the fall, the caterpillar of the Promethea, spins its cocoon within a leaf that it has secured to the twig with strong silk threads. If the cocoon is not snatched up by an observant bird or invaded by a parasitic wasp, the developing winged adult moth can be expected to emerge from its leafy shelter in the late spring or early summer.

Promethea cocoon, Dorbrook Recreation Area, 2/1/2023. Length of leafed cocoon is about 3 1/2 inches.

Promethea moth cocoons, Dorbrook Recreation Area, 2/1/2023. (posted 2/3/2023)

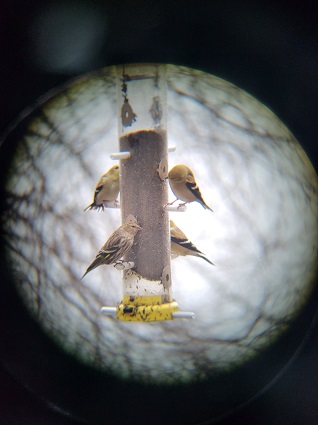

Pine Siskin

We recently had a nice surprise at the Manasquan Reservoir Environmental Center bird feeder window when a Pine Siskin, mixed in with a large flock of American Goldfinch, graced our thistle feeders. Similar in size to the American Goldfinch, Pine Siskins have streaks on their brown bodies and a pop of yellow edging on their wings and tails. They also have a smaller, pointed bill and a short-notched tail.

Siskins are fairly nomadic and some years will have a wide range based on the availability of seed crops. During these irruptive years, a large number of Pine Siskins can be found in New Jersey. It usually occurs when a bad seed crop further north drives them south in search of food. These irruptive years are quite erratic, and there can be a long time between them. This winter only a trickle of these birds have been seen around the state, and only a few of these sightings have been documented with pictures.

This digi-binned photograph (a digital image taken through binoculars) shows a nice comparison between the two species. (posted 1/25/2023)

Inkberry Holly

Pictured above is the Inkberry Holly, or Ilex glabra. Native to the eastern United States, this evergreen shrub lacks the spiny-edged leaves that the American Holly is known for. Similar to the American Holly, Inkberry plants are dioecious and either contain all female or all male flowers. Both a male and a female holly must be within range of each other in order to attain cross-pollination.

Deer tend to avoid grazing on this plant, allowing its evergreen color to brighten up your winter walk. This species typically grows in wetter sites but, interestingly enough, it is also highly adapted to fire. If a fire occurs, Inkberry Holly can push out new growth from its base ensuring its survival.

Inkberry Holly gets its namesake from its dark black berry-like drupes that form after pollination occurs. These fruits are a pivotal food source for birds and other wildlife spending their winters here. Bees and other pollinators make good use of Inkberry flowers and the pollen is considered to be of high quality for honeybees. (posted 1/23/2023)

Squirrel's Drey

Can you guess what animal uses this nest? If you guessed squirrel, you are correct! Squirrels build a nest called a drey. They are often confused for a bird’s nest but a good clue to look for is if there are lots of leaves woven into it and they are usually pretty large. Dreys are most commonly used in the warmer months and are often empty in the winter. Because squirrels are always on the move, they may build two or three nests in one area. These are used as emergency nests to hide from a predator or to store extra food. Some even use them as a temporary rest stop. Next time you see a drey up in the tree, take a few minutes to watch and see if you can spot a furry friend nearby! (posted 1/13/2023)

Razorbills & Dovekies

Razorbill

Dovekie

Winter does not inspire most people to head out to the beach. Its cold weather and high winds can be daunting. However, every day is a good day to head outside. This is especially true for birders and nature lovers this winter as there seems to be an influx of birds in the Auk family (Alcidae) - specifically razorbills and dovekies - coming closer to shore than usual.

Both species can be incredibly hard to spot, often disappearing behind the swell of waves. Razorbills are large – on average 17 inches long - and are easier to spot on the water with their pronounced deep bill, black back, and white belly. The more diminutive dovekies also have a black back and white belly but are just over 8 inches long and have a tiny bill.

The irruptive invasion of these birds close to shore makes for an exciting start to the year. Check out Seven Presidents Oceanfront Park, Long Branch, as well as local inlets, in the hopes of seeing these birds. (posted 1/6/2023)

Greater White-fronted Goose

Do you remember the children’s book Where’s Waldo? Well, look at this picture and see if you can find the goose that stands out. Mixed in with a flock of Canada Geese is a Greater White-fronted Goose. Look for its orange feet, pinkish orange bill, white face patch, black belly splotches, and white side stripe. It was no easy feat spotting this one amongst thousands of Canada Geese recently visiting Thompson Park, Lincroft. (posted 1/6/2023)